Background

Electrochemical interfaces are of critical importance in energy storage and conversion. Characterized by complex and dynamically changing species and structures, their study requires a combination of experimental characterization and theoretical computation. However, existing theoretical methods that can accurately describe these interfaces (such as ab initio molecular dynamics) are extremely expensive. This limits research to model systems on the scale of hundreds of atoms and tens of picoseconds. However, real electrochemical systems are far more complex, simulated on much larger time and spatial scales. In recent years, the rapid development of machine learning potentials (MLPs) has made it possible to significantly accelerate computations while maintaining ab initio accuracy, providing a technical foundation for simulating complex and dynamic electrochemical interfaces. Nevertheless, applying MLPs to the simulation of electrochemical interfaces still presents numerous challenges. On one hand, properties like dielectric response require an accurate description of long-range electrostatic interactions. On the other hand, the dielectric properties of metal electrodes (electronic conductors, ionic insulators) and electrolytes (ionic conductors, electronic insulators) are significantly different, making them difficult for existing machine learning models to describe simultaneously.

Research details

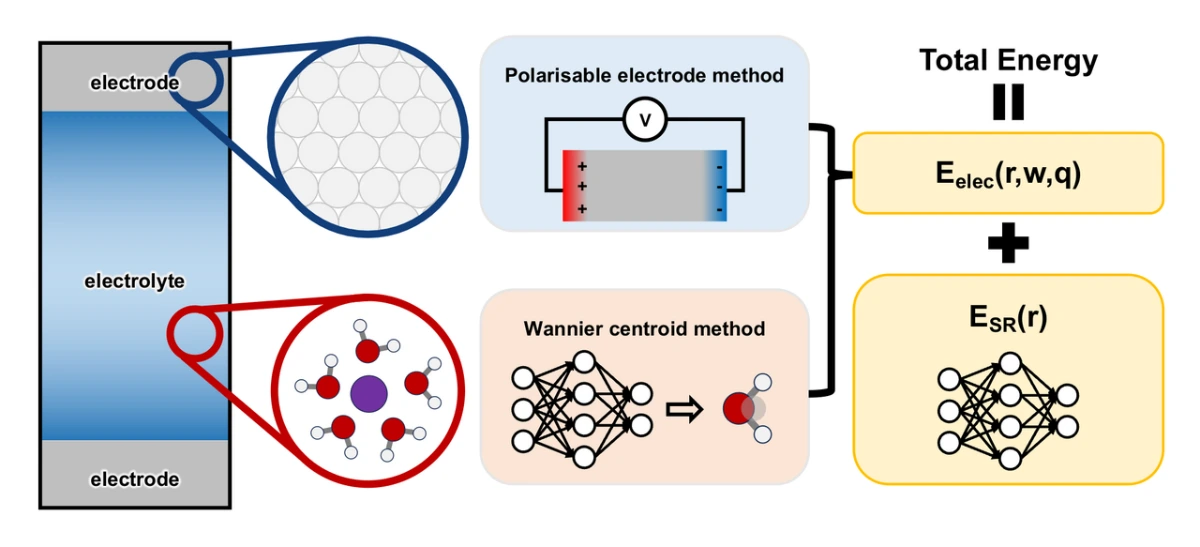

In the electronically insulating electrolyte, the dielectric response is mainly undertaken by the motion of atoms and ions. We therefore choose the Wannier centroid (WC) method to describe this dielectric response, which, from a theoretical perspective, allows reasonable descriptions of both thermodynamic and transport properties. The WC is defined following the previous literature, with its position relative to the associated nucleus predicted from the local chemical environment. This is a reasonable approximation considering the minor effect of electric fields on frozen electrolyte configurations. Nevertheless, this secondary effect can be further incorporated by introducing polarizability terms. In contrast, atomic motion in metallic electrodes is typically negligible, and dielectric response is dominated by electronic polarization. Several models have been developed to describe this electronic dielectric response, commonly referred to as the polarizable electrode approach. Among them, the Siepmann-Sprik model is particularly notable for its wide application. It approximates the charge distributions with spherical Gaussian charges centered on atomic sites of electrodes, yielding a quadratic electrostatic energy functional of atomic charges. The optimal charge distribution, obtained by minimizing this energy, adapts to changes in atomic configurations and boundary conditions, effectively capturing the electronic dielectric response.

The WC method and the polarizable electrode model can be combined to construct a hybrid representation of dielectric response at electrochemical interfaces. This unified framework forms the basis for total energy calculations in the ec-MLP model (see Figure 1). For a given atomic configuration, the positions of Wannier centroids are predicted using a machine learning model for atomic tensorial properties, and the charge distribution in the electrolyte is approximated by point charges located at nuclei and their corresponding WCs. Using this charge distribution, the electrostatic potential at the electrode atom sites is computed. The resulting potential, along with the electrostatic boundary conditions and physical constraints (e.g., constant charge or constant potential), determines the atomic charges in the metallic electrode. The full charge distribution at the interface in our model, comprising both the electrolyte and electrode contributions, enables the evaluation of the long-range electrostatic energy. The residual short-range energy is predicted by a MLP based on local chemical environments, while the electrostatic term is computed as the reciprocal-space contribution in the Ewald summation. In this work, the Deep Wannier model and the Siepmann- Sprik model are employed to describe dielectric responses in the electrolyte and the metal electrode, respectively.

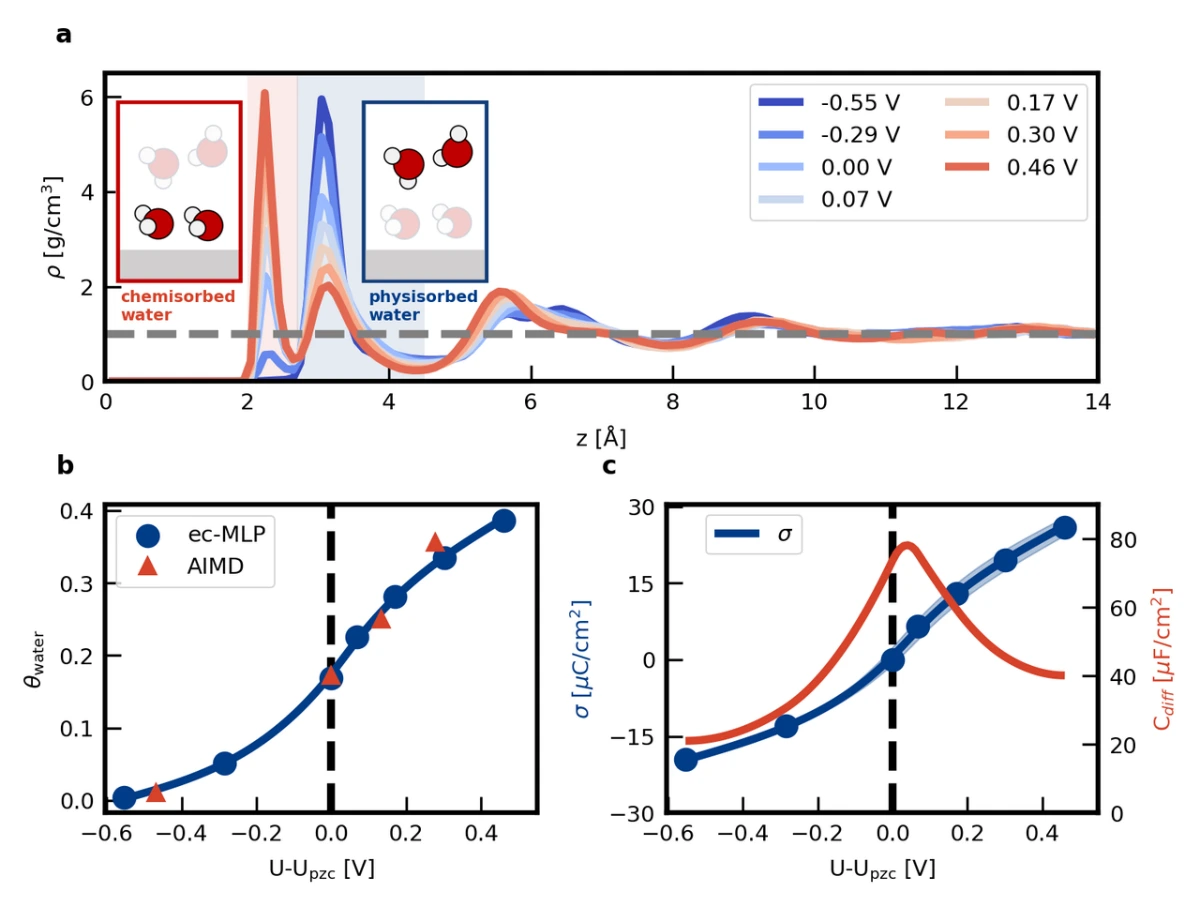

In the following, the Pt(111)/KF(aq) interface is chosen as the model system to demonstrate the validity of the ec-MLP proposed above. This choice is motivated by the widespread utilization of the Pt(111)/electrolyte interface as the model system in both experimental and computational electrochemistry. Most importantly, it is well known in the literature that Pt shows a bell-shaped Helmholtz differential capaci- tance curve [381] caused by dynamic chemisorption of water induced by the applied potential [182]. This phenomenon on Pt highlights the simultaneous importance of electronic structure and molecular dynamics effects, which cannot be accounted for by static DFT or classical molecular dynamics calculation. Using computational settings similar to previous ab initio molecular dynamics simulations, the researchers successfully described the chemisorption/desorption of water at the Pt(111)-electrolyte interface as a function of electrode potential (see Figs. 2a and 2b) and the resulting bell-shaped differential capacitance curve (see Fig. 2c), thus demonstrating the effectiveness of the ec-MLP method.

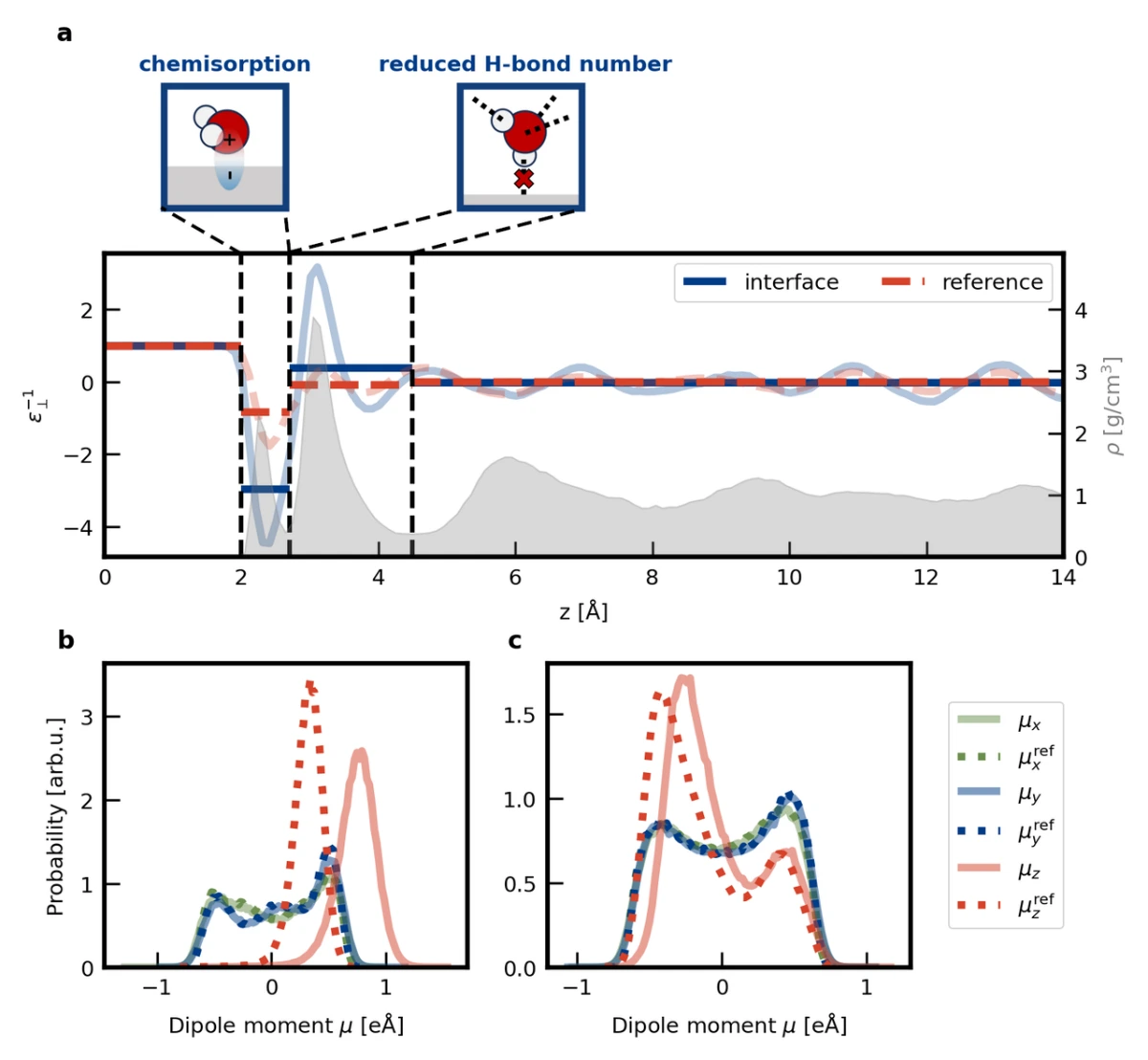

Water in contact with solids shows distinct dielectric behaviors from bulk water, attracting great interest in both experiment and simulation. However, our knowledge about how the dielectric constant varies at the interface is still lacking at the qualitative level. Although some recent MD-based studies provide access to the dielectric profile, i.e., the dielectric constant distribution in the direction perpendicular to the surface, they are limited to the cases of inert interfaces. The calculation of interfaces of high activity (e.g., Pt/water) is still lacking, probably due to the following reasons. On the one hand, simulations with classical force fields cannot describe the interfacial water structures correctly due to the omission of the electronic structure. On the other hand, the timescale for statistically reliable results is not affordable for AIMD simulations.

With the help of the ec-MLP, we can overcome the limitations mentioned above and calculate the dielectric profile at the Pt(111)/water interface for the first time (as shown in Fig. 3a). The results show that in the chemisorbed water region (within 2.7 Å of the metal surface), there is an overscreening of the electric field, while in the physisorbed water region (2.7-4.5 Å from the metal surface), the average dielectric constant is much lower than that of bulk water. An analysis of the dipoles of water molecules in specific regions reveals that the overscreening of the electric field in the chemisorbed water region originates from the increased molecular dipole induced by chemisorption, while the smaller dielectric constant in the physisorbed water region is due to a reduced number of hydrogen bonds. Notably, previous work often attributed the reduced dielectric constant of non-chemisorbed water to restricted rotation. In contrast, this work reveals that electronic polarization has a significant impact on the dielectric response even in non-chemisorbed water.

Acknowledgments

J.-X. Z. gratefully acknowledges Xiamen University and iChEM for a Ph.D. studentship. J. C. gratefully acknowledges funding from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 22225302, No. 92470201, No. 92461312, No. 22021001, No. 21991151, No. 21991150, No. 92161113, and No. 22411560277), the Fundamental Research Funds for the Central Universities (Grants No. 20720220008, No. 20720220009, and No. 20720220010), Laboratory of AI for Electrochemistry (AI4EC), and Tan Kah Kee Innovation Laboratory (Grants No. RD2023100101 and No. RD2022070501). J.-X. Z. also thanks Dr. Jia-Bo Le, Dr. Xiao-Hui Yang, Dr. Katharina Doblhoff-Dier, and Dr. Jun Huang for their helpful discussions. The authors thank Dr. Linfeng Zhang, Dr. Han Wang, and DP community for helpful discussions and technical support.

Full text

https://journals.aps.org/prl/abstract/10.1103/48ct-3jxm

Github

ec-MLP will be released as a module in ai2-kit: https://github.com/chenggroup/ai2-kit: